Born circa July 4, 1920, Pike Road Community, Montgomery County, Alabama, Died October 30, 2006 Montgomery, Alabama

One of the most highly regarded American self- taught artists began life as the son of a sharecropper and farm overseer on the Rittenour farm. Known as “Mose T”, as he signed his paintings, he was the youngest of seven sons born into the Ike Tolliver family of twelve children. He attended Mt. Olive school briefly through the third grade. “I didn’t like school. I remember I wanted to be outdoors working with my older brothers or even stacking wood….One thing I remember about our farm house –it was just a shack, but my Mama had pictures all over the walls.”

Tolliver worked through his teen years for a truck farmer gathering and selling produce. Then, after his father had died and his mother was elderly, he moved with her into the city of Montgomery and lived in the same house. Mose became a gardener and took care of many fine yards. Known for having an artistic flair for landscaping, he was given free rein by some of his clients to arrange bedding plants. Occasionally, he also painted houses inside and out, and was a jack- of-all-trades for repair jobs involving plumbing and carpentry.

Mose met and married Willie Mae Thomas in the early 1940’s and fathered eleven children, seven sons and four daughters. Two other children died in infancy. Mose worked “on and off for years” with McLendon Furniture Company, mostly sweeping out the shipping and delivery area early each morning. There in the late 1960’s, a crate of marble fell from a forklift and crushed Mose’s left ankle, damaging leg tendons and muscles which left him unable to walk without assistance.

A couple of years after the accident, and after a period of drunken depression, Mose was encouraged to try oil painting by Raymond McLendon, one of his former employers. McLendon painted with oils on canvas and Mose had, on occasion watched him and his brother, Carlton, paint. Noting his fascination, McLendon tried to persuade Mose to take lessons at his expense, intending to provide an alternative pastime to Mose’s drinking alcohol. Mose elected to teach himself and painting became a routine activity for him. It was a rehabilitative experience. At first he painted birds, flowers and tree forms, later adding people and other animals. “I probably would never have painted if I hadn’t gotten hurt. I would still be working with plants and yards.”

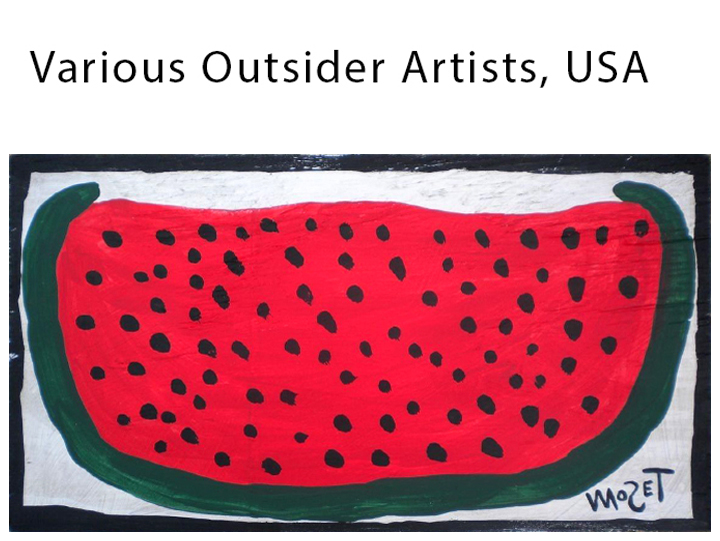

Tolliver began to obey an inner compulsion to create art in his own unique way at an amazing rate. Mose began to paint on any surface–furniture, scraps, plywood packing crate sides, Masonite, metal trays, board remnants, old bureaus, table tops, throw away chairs or other abandoned surfaces given to him. Mose used what he calls “pure paint,” house paint–oil based at first, and then water-based latex. Although his palette almost always was limited to two or three hues from the cans available at hand, Mose’s color schemes were generally harmonious and sophisticated. His inventive use of a variety of improvised hanging devices (and later metal can rings) on his work indicated a natural creativity that often goes hand in hand with poverty and necessity.

His work first caught the attention of people walking past his house on Morgan Avenue where Mose began his painting, but none sold. The,n after moving to his present Sayre Street home, his front porch became a virtual gallery with Mose offering to sell paintings to anyone who admired them. An early admirer who brought his work to public attention was Mitchell Kahan, former curator at the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts. In 1981, the museum mounted a one-man exhibition of Mose’s work. In an essay published in the exhibition brochure, Kahan pointed out the element of humor in Mose’s work, “…the naivete of the improbable and bizarrely constructed animals is comical in a charming way. The humor… results from the unintentional discrepancy between the painted image an the real-life source…Often the humor is linked to elements of fantasy and eroticism.”

In the first article published about Mose in February 1981 in the Montgomery Advertiser, he is quoted as saying, “I’m not interested in art. I just want to paint my pictures.” In the same article the late Dr. Robert Bishop, Director of the Museum of American Folk Art said of Mose’s paintings, “You can hang him beside a Picasso, and you have the same kind of creativity and deep personal vision.

|